By Jane Hutton

Questions

Historically, what role did health surveys play in developing government policy for HIV/AIDS response in Johannesburg? Today, how is health data impacting the response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Discussion

Under apartheid legislation in South Africa, government policy was intertwined with population data. The national government categorized people by race, assigning each to a group according to parentage and physical features. These categories were recorded on birth certificates and used to restrict populations to certain areas using a series of pass laws. Cities were designed solely for white habitancy, which affected countless other government policies related to the city that were informed by population data. Creating this system of social statistics and partitioning maps according to that data was how the apartheid government segregated the population to assert and maintain control over the oppressed black majority.

For complex reasons, however, the immediate post-apartheid, democratic administrations brought a change in how the government used population data that nevertheless bore the legacy of the apartheid era. Specifically, in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, there was a blatant disconnect between the findings of health and social surveys and government policy. For one, the new democratic government inherited most of the apartheid structures intact, leaving politicians caught between addressing the incipient virus and political transition efforts. The apartheid government was designed to control certain populations while simultaneously excluding them from social services. After apartheid, Johannesburg, like other cities, was underfunded and under-resourced for the sudden increase in people it needed to serve (Thomas 2003, 191). Faced with the difficult task of restructuring the government while maintaining operations, the Johannesburg city government found itself constrained by the old bureaucracy of the apartheid regime. Mbali shows that this incapacity to respond to a crisis so large may have contributed to the national government’s failure under Mbeki, who instead hoped that the crisis would somehow solve itself without government intervention (Mbali, 2004, 107).

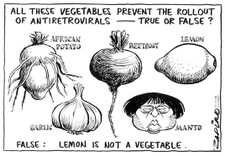

Cartoon satirizing the South African Health Minister’s recommendations for treating AIDS.

Successor to Nelson Mandela, President Thabo Mbeki promoted AIDS denialism, the belief that AIDS is not caused by HIV and that antiretroviral therapy is not effective as a treatment. Other high ranking government officials also publicly voiced denialist views, including Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, who the president appointed to be Minister of Health. Tshabalala-Msimang continually advocated solving the AIDS crisis with general improvements to public health, like eating more vegetables. Mbeki’s presidency lasted from 1999 until 2008, and although antiretroviral therapy started being available in South Africa starting in 2004, the roll-out was slow and inadequate given the size of the problem by that time. Mbali’s thesis is that this denialism was rooted in a rejection of a colonial discourse that depicts African sexuality as something diseased and sinful (Mbali 2004, 111). According to this understanding, Mbeki’s denialism could be interpreted as a direct rejection of the apartheid regime that upheld this racist medical discourse. Thus, the international response to HIV/AIDS appeared to South African leaders as a continuation of Western stigmatization of African sexuality, resulting in a rupture in the relationship between government policy and population data gathered from social surveys.

Another cartoon that satirizes Mbeki’s AIDS denialism.

Despite the government’s denial, researchers were still conducting surveys to understand the crisis. And despite not actually impacting government policy, many of the surveys had a particular focus on discovering how a response program could be more effective. Though it does not have the highest percentile prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the country, Johannesburg, being the most populous city in South Africa, does have the greatest number of adults that are HIV positive. One particular survey conducted in the late 1990s in Carletonville, a mining community just outside of Johannesburg, exemplifies this. The data collected by Gilgen, et al. are disaggregated into numerous categories, including alcohol consumption, male circumcision, and migrancy, in order to better understand HIV risk factors (Gilgen, et al 2000, 20). The greater Johannesburg region has been the focus of many studies due its large number of at-risk individuals, including sex workers and mine workers. However, despite what researchers concluded to be necessary policy interventions, Johannesburg struggled for years to implement a successful HIV/AIDS program. One issue the Johannesburg city government faced in adequately responding to the crisis relates to the demographic face of the virus. As Thomas discusses, urban communities with large areas of informal settlement, like the Soweto township, experienced a higher rate of incidence (Thomas 2003, 188). It is precisely these informal areas that the apartheid regime excluded from accessing social services, a gap that the new democratic government of Johannesburg suddenly had to account for.

Since Mbeki left office, South Africa has significantly increased its HIV/AIDS response efforts and is nearing international goals for HIV/AIDS. Surveys continue to have a similar focus on risk analysis by investigating knowledge of and attitudes toward testing, such as the study done by Chimoyi, et al. (Chimoyi et al 2015). These distinctive layers of social surveying related to the HIV/AIDS crisis follow the evolution of the government’s response. First, when government intervention was limited, researchers focused on social factors related to risk of infection. Now that there is more effective testing and treatment, surveys are studying the social factors related to attitudes toward being tested. Considering the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS, these attitudes are important to understand in order to maximize intervention effectiveness. One Johannesburg study showed that, in addition to stigma and discrimination, factors such as marital status, occupation, and location of employment and residence were significantly inhibiting HIV testing (Nyasulu 2014, 18). Surveys such as these provide important context for intervention attempts that have helped guide testing and treatment programs in targeting their efforts. Advanced technologies such as the Optima HIV model have been used to predict the spread of HIV/AIDS in Johannesburg to help the city understand how to achieve its targets (Stuart, et al 2018).

With the current COVID-19 pandemic, South Africa is redirecting its HIV/AIDS infrastructure. The Johannesburg-based Aurum Institute, a research and health care nonprofit that typically handles HIV and TB patients, has mobilized its staff to help COVID-19 testing and contact tracing. The Institute is also studying treatments and vaccines, and it will monitor the efficacy of the nation’s response to the current pandemic (Nordling 2020). Health experts who have experience handling HIV/AIDS and TB in South Africa are hoping that the similarities between the control measures will help the country contain COVID-19. However, there are worries about these same preexisting conditions and the effects they may have on the spread of the pandemic. Immune deficiency in people that are HIV positive and lung damage caused by TB may make these populations more vulnerable to the virus. The national government has started using mobile tracking technology to facilitate contact tracing, which will also be used to identify vulnerable areas (Mahlangu 2020). While most information on South Africa’s response to COVID-19 is at a national level, the pandemic is specifically relevant to Johannesburg because it is the largest city in South Africa, posing a particular threat to Johannesburg because of population density and HIV/AIDS and TB prevalence. As previously discussed, Johannesburg has a large population of HIV-positive adults, and the mine workers experience higher rates of lung problems due to occupational hazards. To protect these vulnerable populations, the city government closed all public facilities starting in mid-March and deployed clinical teams to support those most at risk. The city is utilizing a tracking and tracing approach to contain the spread and proactively targeting its response to the most at-risk areas, like informal settlements (News24 Wire 2020).

Despite the initial delay in Johannesburg’s response to HIV/AIDS, the city government has successfully bridged the disparity between survey data and policy. Several models conclude that Johannesburg is well-positioned to achieve the international 90-90-90 HIV/AIDS strategy whereby 90% of people living with HIV are aware of their status, 90% of those aware are being treated, and 90% of those being treated have viral suppression. This same thoroughness in addressing HIV/AIDS is currently being utilized in minimizing the spread of COVID-19, demonstrating the transformation in the government’s use of population health data.

Sources

Gilgen, Denise, Brian Williams, Catherin Campbell, Dirk Taljaard, and Catherine MacPhail. The Natural History of HIV/AIDS in South Africa: A Biomedical and Social Survey in Carletonville. Johannesburg: CSIR, 2000.

Mahlangu, Isaac. “Government to Start Using Technology to Trace Covid-19 Carriers.” SowetanLIVE. SowetanLIVE, April 1, 2020. https://www.sowetanlive.co.za/news/south-africa/2020-04-01-government-to-start-using-technology-to-trace-covid-19-carriers/.

Mbali, Mandisa. “AIDS Discourses and the South African State: Government Denialism and Post-Apartheid AIDS Policy-Making.” Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 54, no. 1 (2004): 104–22. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2004.0023.

News24 Wire. “City of Joburg Closes All Public Facilities, Including Pools, Theatres and the Zoo.” The Citizen, March 19, 2020. https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/government/2257497/city-of-joburg-closes-all-public-facilities-including-pools-theatres-and-the-zoo/.

Nordling, Linda. “South Africa Hopes Its Battle with HIV and TB Helped Prepare It for COVID-19.” Science, April 15, 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/south-africa-hopes-its-battle-hiv-and-tb-helped-prepare-it-covid-19.

Nyasulu, Peter, Ndumiso Tshuma, Keith Muloongo, Geoffrey Setswe, Lucy Chimoyi, Bismark Sarfo, and Dina Burger. “Potential Barriers to Rapid Testing for Human Immunodeficiency Virus among a Commuter Population in Johannesburg, South Africa.” HIV/AIDS – Research and Palliative Care 7 (2014): 11–19. https://doi.org/10.2147/hiv.s71920.

Stuart, Robyn M, Nicole Fraser-Hurt, Cliff C Kerr, Emily Mabusela, Vusi Madi, Fredrika Mkhwanazi, Yogan Pillay, et al. “The City of Johannesburg Can End AIDS by 2030: Modelling the Impact of Achieving the Fast-Track Targets and What It Will Take to Get There.” Journal of the International AIDS Society21, no. 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25068.

Thomas, Elizabeth. “10 HIV/AIDS: Implications or Local Governance, Housing, and the Delivery of Services.” In Emerging Johannesburg, edited by Richard Tomlinson, Robert A. Beauregard, Lindsay Bremmer, and Xolela Mangcu, 185–96. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2003. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/georgetown/detail.action?docID=1619057.