By Dohee Kang

COVID-19 Timeline in South Korea, 2020

1/20 First confirmed case in Korea

2/04 Entry ban of foreigners traveling from Hubei province in effect

2/09 Patient No. 31 of Daegu attends a service at the Shincheonji Church

2/16 Patient No. 31 of Daegu attends another service

2/20 38 cases emerge from the Shincheonji Church

2/20 First COVID-19 death in Korea

2/21 First two confirmed cases in Busan

2/24 Confirmed cases in Korea second highest in the world

2/23 Threat alert level raised to the maximum

2/28 Daily new cases peak at 813

3/13 First COVID-19 death in Busan

3/21 Recommendation to close religious facilities, gyms, and nightlife venues for 15 days

4/01 Mandatory 14-day quarantine for all entries in effect

3/15 New cases fall to two digits

4/05 New cases under 50

4/09 Academic semester begins online after delays

4/15 Parliamentary elections held

5/02 Patient No. 66 of Yongin visits clubs in Itaewon, Seoul

5/05 Korean Baseball Organization season begins

5/06 Social distancing rules relaxed

5/09 Seoul orders nightlife establishments to suspend operations

5/11 Ministry of Education delays the opening date for schools to 5/20

5/12 Busan orders nightlife establishments to suspend operations

5/16 161 Itaewon-related cases confirmed so far

Table of Contents

Introduction

As of May 16, 2020, there have been 11,037 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 262 deaths in South Korea.[1] The first confirmed case in the nation dates back to January 20.[2] There was a drastic spike in new cases in the second half of February, after “Patient No. 31,” a member of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony, attended multiple church gatherings in Daegu despite showing symptoms. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) told a briefing on March 14 that 5,013 (62%) out of the 8,086 total confirmed cases thus far were linked to the Shincheonji Church cluster.[3] By April 18, Shincheonji-related cases numbered 5,212.[4]

During this wave of outbreak, new infections in South Korea peaked on February 28 with 813 cases.[5] In two weeks, by March 15, new cases were down to two digits.[6] The country’s relative success in containing the virus at this time can partly be attributed to its rapid and extensive testing and isolation of exposed people. Within two weeks of Patient No. 31’s testing, the city of Daegu tested 7,913 (72.5%) of the 10,914 church members in the city, the percentage reaching 99.8% in another week; during those couple of weeks, the national government tested 192,634 (98.7%) out of the 195,162 church members across the whole nation.[7] In addition, drive-through testing stations were devised and erected throughout the nation starting February 23, offering fast and affordable tests.[8] The travel routes of each confirmed patient have been traced thoroughly and shared with citizens for a limited time, such that those who might have been exposed could seek testing. (For an example, see Busan’s Pandemic Snapshot on this website.)

Epidemic Curve of COVID-19 in South Korea (Wikipedia)

Since the beginning of the outbreak, South Korea has never imposed a lockdown or a curfew, keeping its economy open and leaving it up to its citizens to practice social distancing. As infections rose domestically and globally, the Prime Minister recommended on March 21 that places of worship, gyms, and nightlife facilities close for 15 days.[9] On April 1, a mandatory 14-day self-quarantine for all individuals entering from overseas came into effect.[10] After multiple delays, primary and secondary schools began their spring semester online on April 9.[11] As the country saw a gradual decrease in new cases, in-person parliamentary elections were held on April 15. The turnout was the highest (66.2%) since 1992 despite the pandemic, and no new case emerged from the event.[12] On May 5, the Korean Baseball Organization began its season in empty stadiums, having made broadcasting deals with major television channels in countries temporarily deprived of sports events.[13]

Having brought down new cases to single digits, South Korea began to relax its social distancing rules from May 6, re-opening businesses that had been closed and allowing events and gatherings.[14] Right away, the country faced a new spurt of cases. Over the holiday season from April 30 (Buddha’s Birthday) to May 5 (Children’s Day), Patient No. 66 of Yongin, a city in the Seoul Capital Area, visited multiple clubs in the Itaewon area of Seoul. Confirmed cases have been on the rise since. Consequently, cities have ordered bars and clubs to close, and the Ministry of Education delayed the re-opening date for schools.[15] As of May 16, there have been 161 Itaewon-related cases.[16]

Epidemic Curve of COVID-19 in Busan, South Korea (Wikipedia)

Busan Metropolitan City, the second largest city in South Korea, has 3.4 million people. It is 88 km (54 mi) away from Daegu, the site of the Shincheonji outbreak. The first two cases of COVID-19 in Busan were confirmed on February 20.[17] As of May 16, there have been 141 confirmed cases and 3 deaths in Busan, with 11 patients undergoing treatment.[18]

The Interviews

My interviews about the pandemic experience in Busan were conducted individually with three middle-aged residents, whose names will be anonymized as A, B, and C to protect their privacy. A and C are female, and B male. They all happen to be based in the Haeundae district, which is known for its namesake beach. Many of the initial COVID-19 cases in Busan were from Haeundae, the most populous district in the city with 11.6% of the city’s population.

The first round of interviews was conducted on April 7 KST, and follow-ups on May 9 KST. By the time of the first set of interviews, Busan had seen a steady fall in new cases for a month. There had been 122 cases and 3 deaths, and 8 patients were undergoing treatment.[19] Between the first interviews and the follow-ups that took place about a month later, 16 additional cases arose with no change in the death toll.[20] News about the Itaewon cluster had just emerged.

Interviews were conducted in Korean via voice calls on KakaoTalk, a messaging application widely used in the country. Below are excerpts from the interview transcripts I translated, organized by topic and followed by some images shared by the interviewees in mid-May.

The Virus

First time hearing about the virus

A: I didn’t think much of it. I didn’t expect [the virus] to be so infectious and spread so widely. I just thought it’d be controlled within China. I had also read that the virus was released from a lab in Wuhan––I thought it would start and end around there.

B: Last November? December? I first heard of it as “the pneumonia of unknown causes” on the news.

C: Yes, on the news, that the virus was spreading from China. At first it wasn’t spreading much in Korea, but there was an outbreak at a church, leading to an explosive increase in infections. I didn’t expect it [to spread so widely]. I just thought it’d be like a bad flu… but not this bad! I didn’t think the whole nation and the whole world would shut down, that flights would be canceled. I just thought old people would have a hard time, like during a flu season.

Past epidemic experiences

B: In the past, you see, there’ve been outbreaks, like SARS, MERS, Zika, Ebola… But this is the worst one. During SARS, there was no social distancing. This one’s very infectious, spreading so fast all over the world and creating an atmosphere of fear. Each country is trying to fend for itself. Daily lives and economic activities are greatly affected. [COVID-19] is the most widespread of all epidemics I’ve lived through. During MERS, there was an outbreak in Korea, at hospitals. There were deaths, and it was a problem. The death toll was around 30. Those infected were one-hundred-something. Two hundred. It became politicized in Korea at the time, leading to the creation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and systems for managing future epidemics. Manuals, too. When the virus started in China this time, the first thing [the KCDC] did was to have companies develop diagnostic reagents, which they authorized in record time. Korea is advanced in its technology for developing reagents. With the reagents, we were prepared. When the pandemic began in Korea, we started testing with our own diagnostic kits.

C: During MERS, they said it was infectious too, but its infection rate wasn’t nearly as high, and we knew that those known to have it infected others. But with [COVID-19], some infections are asymptomatic, and I think that’s the most difficult part. The spread could be stopped quickly if the infectious patients were symptomatic, but people are unknowingly spreading the virus. This is on another level when compared to MERS, I think.

Information

A: Yes, from the news.

B: The news sources update us on Europe, the U.S., the whole world. I’m checking statistics across the world on the internet.

C: I usually do searches on the internet on my phone. […] When things were bad, I would watch the news as soon as I wake up and all day long. For details, I would do searches on my phone, on Naver*. I would check for new articles as well.

*A Korean search engine.

The Everyday

Measures taken at buildings

A (May 9 follow-up): My mother’s nursing home only hires caregivers who’ve tested negative. A thermogenic camera is set up at the entrance, and you can only go in with a reservation confirmation. You can’t enter without a mask on and need to sanitize your hands at the entrance. They allow one guardian per patient and have banned face-to-face visits. Probably because infections could be deadly for old people with underlying conditions. A hospital employee receives supplies and food from the guardian at the entrance and brings them over to the patient. There used to be two entrances, but they’ve blocked one to check temperatures and sanitize hands. Outsiders can’t even use the restrooms. In the beginning of the coronavirus [outbreak,] they’d ask if I’d been to China, then if I’d been to Daegu, and these days if I’d been to Itaewon.

B: Amenities like gyms [at my apartment building] have been closed for over a month. On the elevators, films that kill microbes are put over the buttons, and hand sanitizer is placed. They’ve installed a temperature detector at the front desk to catch whomever has a fever. There’s also sanitizer next to it. And they clean and disinfect as well. That’s my apartment but most apartments are like this. Any public place you go you will find hand sanitizer.

C: [My apartment] placed hand sanitizer, and they tell us how many times they’re disinfecting the building per day. We used to have both front and back entrances, but they’ve closed the back one. So people only use the front entrance, where they’ve installed a temperature detector.

Interactions with others

A: Recently my father was feeling a bit depressed, so I drove him through the cherry blossoms. They’re so pretty on Dalmaji-gil. My father loved it so much. After that, we had lunch at a place where people usually get numbered tickets, but it was completely empty. I brought him to my new place for coffee and then he left. But he said he didn’t want to leave. Because the ocean was so beautiful.

B: People avoid meeting up as much as possible. It makes people uncomfortable, talking with masks on. “Until the day we can drink with masks off!” is a commonly exchanged phrase. But people do meet when necessary. And young people usually won’t have severe symptoms, so some gather. People don’t avoid important people in their lives; but if unnecessary, they usually avoid meeting up.

C: [My interactions have] been reduced to one tenth. Normally I see a lot of friends, but we don’t meet anymore, and I can’t go to the gym either. So I just grocery shop and see my best friend once in a while, so my outings have been reduced to one tenth.

Daily activities

A: My daily life started to be affected [by the virus] around mid-February, when it started spreading in Korea. I couldn’t visit my mother at the hospital, nor could I see my friends. My unit is undergoing repairs, so workers come here. I just moved in and don’t have cooking tools, so I eat out. At restaurants, I sit close to the entrance and eat fast. For two weeks, the repairmen weren’t available, since the chances of infection were high. I watch one movie every day on internet TV. I also read. I take walks at night after dinner.

B: Busan, the city of Busan where I’m located, has a population of… 6 million? Here, we haven’t had new cases in the past few days. So far we’ve had about 120 total cases. But in the recent 4-5 days, we haven’t had new infections. Once in a while, there would be one infection and then none again––so it’s become quite stable. But almost everyone is wearing a mask outside. […] In Korea, restrictions have been too loose from the beginning. No place has been ordered to close, just… So people are eating out everywhere––that’s also the case in Seoul and the rest of the country. People are given autonomy. So people are eating, gathering, drinking… a mess. When I do eat out I have the windows open if there are any. Haeundae is a touristy place, so people come here from all over the country. Many infected patients in Busan so far have been connected to Haeundae. Their routes often include Haeundae or they live here. Haeundae is very populated so a bit dangerous. Since masks have to be taken off when eating, restaurants here are the riskiest of places. But had infections in Busan been bad like in New York City, only take-outs would’ve been allowed. We don’t have many cases now, having controlled the early cluster, so people are eating out all over the city. […] My self-quarantine period is over, so I do go outside. I walk on the beach. I visit my mother.

B (May 9 follow-up): I do go grocery shopping often. I need to get fruits, drinks, yogurt, and so on.

C: I don’t work out at home… It’s hard to do it by myself so I circle Dongbaekseom* three times. We’re allowed to go on walks, so I tell myself, “I should go on a walk.” But when I tell myself, it’s suddenly windy. I tell myself, and it rains. I tell myself, and I’m sleepy so… I’ve only been a few times.

*An island near the Haeundae Beach.

C (May 9 follow-up): I cook at home mostly, whereas I would eat out a lot with my friends before. But these days, as our country has gone into “distancing in daily life,”* I started seeing friends a little more often. But [after the Itaewon outbreak] I need to be careful again!

*On May 6, Korea entered the “distancing in daily life” phase, allowing events and re-opening businesses that were closed as per recommendation by the government.

Dalgona Coffee

A: I saw it on the news. But I don’t put sugar in my coffee, so I just use my espresso machine. […] You combine sugar, instant coffee, and water, and stir four hundred times. That’ll make it foamy. Then you pour milk into it, and it’s supposed to be sweet and delicious. People are so bored while stuck at home that they are willing to stir four hundred times. And you know how having something sweet makes one happy. So Dalgona makes time pass and relieves people of depression. I heard that people outside of Korea started making it too.

C: My daughter made it and sent me a photo. But you have to stir four… million times! I don’t have an electric whisk so I never had it.

Collective experience

A: Let’s see, when did it start getting bad? Around mid-February. [The virus] started spreading in Korea, and people were scared. There was not a single person on the Haeundae beach. Restaurants were completely empty, too. Even at those popular restaurants where people get numbered tickets or line up––no one. Visits at hospitals and nursing homes were banned. By now, after the peak, people are still social distancing but also going outside, taking walks. But in mid-February, everyone was scared and stuck at home. By early March, staying home became suffocating for people. So they started going on walks, because open spaces are a little better, right? Before that, people feared stepping out. […] I heard that since people are staying home, television viewing rates have increased. […] Bookstores are all open here. People just don’t go much. […] Ever since it was broadcast that early infections happened at restaurants, where people sit in close proximity and face one another, the number of people eating out has decreased drastically. But it’s been increasing little by little. In Busan, there are only one or two new cases each day nowadays. […]

Restaurants have been struggling a lot, so the building owners have been lowering rents voluntarily. To ease collective struggles. […] There’ve been a lot of patients in Daegu because of the Shincheonji Church. People have felt so much gratitude toward the medical professionals there. The owner of a chicken restaurant in Seoul cooked up thirty chickens and called a taxi to have them delivered, but the driver was afraid to go to Daegu since it was a hotspot then. So the restaurant owner hired another person to deliver the chickens, making sure they were still hot by the time they reached Daegu. It’s been nice to see such genuine, heartwarming gestures.

A (May 9 follow-up): Indoors, [people wear masks.] When outside, like in the mountains, people take them off. When walking on the streets, people would take them off sometimes, because it’s so uncomfortable––KF94* can get really uncomfortable when it’s hot outside. […] [When cases were high,] people didn’t take them off. The number of new cases has been in single digits until a few days ago, right? So people have been taking them off more. But because of this outbreak in Itaewon… You know about it, right? Sexual minorities** are being scapegoated––it breaks my heart.

*A Korean standard for filter masks

** The term currently used in South Korea for the LGBTQ community

B: In the past 3 days, there’ve been 47, 47, and 51 new cases. Almost 45% of them are students studying abroad who’ve come back. But who can blame them? If these students get infected abroad, they often can’t receive treatment, so they come to Korea, where they’ll get good treatment. That’s inevitable. […] Entering Korea is fine, but entering while hiding symptoms or not quarantining oneself afterward… There was a student who managed to enter the country with a fever by taking a bunch of fever reducers. Right now, Asiana and Korean Air are not allowed to take passengers with a fever from the U.S., so he took fever reducers. He tested positive the day after he arrived. […]

We’re not forced to be on lockdown, nor work from home, nor quarantine ourselves. Even social distancing is only a recommendation. Religious gatherings are asked to be held online if possible; if in-person, social distancing is practiced, and masks are worn. Schools have gone online. But restaurants, coffee shops, clubs, after-school classes, superstores, department stores, retail stores, offices, and factories are all in operation as per usual. The main changes are that people avoid going outside or meeting in person as much as possible, fearing infections, and that they wear masks and wash hands thoroughly. Customers at stores and restaurants have decreased, but these places do operate and have customers. Popular restaurants still get many people. There aren’t as many people on the streets, but still quite a lot. There haven’t been huge inconveniences or changes in day-to-day life here in Korea. Everyone was worried during the Daegu outbreak, but since new cases dwindled in a relatively short time, people came to trust the government and medical professionals and grew confident in our ability to control the virus. People are careful, but not fearful.

B (May 9 follow-up): I wear a mask indoors––and outdoors as well, but some people don’t wear masks outside these days. At parks, beaches or mountains, ten percent don’t wear them, and ninety percent do. Same on the streets. In indoor spaces, like stores, between ninety and one hundred percent. But when eating, one must take the mask off, so I think that’s the most dangerous occasion.

C: From the beginning, we were told to stay home––that’s been the toughest part, but as time goes on, we’re getting used to it. I’m learning to spend time at home wisely. At first, everyone was having a hard time, but gradually people got used to it––to eating at home, for example. Not having a student at home helps. I got used to it… I learned that I could stay home if I had to.

C (May 9 follow-up): When people are out they tend to be out in nature––walking on the beach, for example. It seems there are more people going on walks these days.

Korean Response

Communications from the government

A: Yes, I get their texts everyday. If there is a new case, I’m notified not only of its area but also of the routes of the patient. The identity of the person is not revealed–-just something like “25-year-old male”––so as to protect privacy. It shows where this person went and when, encouraging those who overlapped to get tested.

B: When I entered the country in February, they installed an application on my phone for me at the airport. Things weren’t so bad at the time so I wasn’t required to self-quarantine. I just had to– The application asks you questions everyday: “Do you have a temperature above 37.5 Celsius?” “No.” “Do you have chills?” “No.” “Do you have a sore throat?” “No, no.” I just had to send answers every day. But I didn’t for one day or two, and got a call from the National Health Insurance Service asking, “You got the app, right? Why aren’t you sending answers?” This shows that they were actually monitoring. This wasn’t even the time when the [14-day] self-quarantine was enforced––we were allowed to go outside. They just asked us for our self-diagnosis. Then from late March or early April, the self-quarantine became mandatory. If you break it or lie, you have to face a fine of ten million won (~$8,060) or jail time of up to one year. People quarantine at home or at hotels. They give you 400,000 won, which is around 400 dollars, as well as water, food, rice, and snacks to sustain you [for 14 days]. No other country gives this much as far as I know. Look it up on YouTube. If you test positive, treatment is free, almost free. So is testing.

C: Almost everyday, the routes of confirmed patients are sent to my phone. At first, I would get routes of patients all over Busan; when there were too many cases, I’d only get those from Haeundae. […] Other than the routes, I also get information about sports centers closing and for how long––information like that keeps coming in. By texts.

C (May 9 follow-up): These days, I’m getting texts encouraging all those who went to Itaewon to get tested.

Korean government response

A: [The government] didn’t order restaurants to close. No restaurants closed. But people avoid going. […] The government did encourage places like gyms to close, after infections occurred in them. People avoid them. They’re scared. The government didn’t enforce anything much. At first, people didn’t go to places like clubs, but young people felt suffocated and started going out. There’s been a view that young people don’t have symptoms as much and recover easily, so a lot of young people were heading out. The government then asked people to refrain, and they listened. But since sales have decreased for a month, some clubs are saying they’d reopen––I don’t know if that’ll end up happening.

B: And––this is important about the Korean government––the government has reported all the information to its people at daily briefings, in a transparent way, without lying about numbers. You know there are asymptomatic people, those infected but without symptoms. Those people––China didn’t even count them as positive cases at first. But Korea included all of them in the counts. They never made any effort to make numbers look smaller. Anyone who has the virus is included. They include them all. They test them all and treat them all. And deaths––there are so many ways to distort the number. In the case of Japan, there’s been an enormous number of infections, but they haven’t been testing much. When people die, they say “they died of pneumonia” or “died of diabetes” or “died of hypertension.” See, it can be done. And it’s finalized with cremations. Numbers can be tweaked readily if desired. But Korea has been transparent and truthful in gauging, reporting, and counting the cases. So the people trust [the government]. Because the people trust, they don’t hoard. […]

In Korea, restaurants, bars, churches, all sorts of places where people gather––none of them have been forced to close so far. Even Daegu during its outbreak was not locked down. So [the government] has been managing the pandemic in a way that befits a democratic society. There are risks that come with this approach, of course, but Korea has used IT to manage the pandemic thoroughly and actively tested all those who might have been exposed. I think tests are only about 40,000 won. Basically free. Treatments are free, too. Korea has been treating actively, testing actively, and contact tracing early on. That’s how we’re controlling the virus successfully. That’s why they keep holding us up as an example––we’ve managed everything without lockdowns. All over the world– Have you seen that clip of Kang Kyung-hwa (the Foreign Minister) on BBC? Check out Sohn Mina’s interviews on Spanish media on YouTube, too. She’s very thorough in explaining the government response. According to [this journalist], [Korean] citizens have also shown a high level of civic awareness, actively participating in preventative measures and refraining from hoarding. Of course, there are those who go out drinking and go clubbing or escape the mandatory quarantine. But most people have practiced social distancing well. They’re also wearing masks and washing hands faithfully. The government has done a good job with manuals and recommendations. So far, it’s worked hard and done an exemplary job. […]

The death toll is low in Korea, too. They tested thoroughly in the beginning and treated early on for free. Testing when one already has pneumonia is too late. Here, they usually start treatment as soon as one’s been exposed, so deaths have been low in number.

C: The initial preventive measures were bad. But more than the government, the doctors and nurses showed such dedication, which I think ultimately controlled the virus. Credit goes to our intelligent doctors and system. I also think the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did a very great job.

Entries from China

A: If they had controlled entries from China in the very beginning, whether Chinese or Korean, I don’t think the virus would’ve spread to this extent in Korea. But our government is pro-China, so they didn’t stop the entries. But look, China’s blocking us now!

B: Another thing that the Korean government did: Unlike Italy, Spain, the U.K. or China, Korea only banned entries from Wuhan, allowing entries from all countries including the rest of China. That’s still the case now. Japan canceled its visa exemption for Koreans. Korea, on the other hand, have been open to the world. We haven’t banned entries from any country so far. [This policy] is very inclusive. Despite the risks, we’re honoring the ideals of globalization and not preventing interactions among nations.

C: They should’ve blocked the entries at the very beginning.

Privacy issues

A: I heard that [the release of patient routes] is unthinkable in other countries, due to privacy issues. In Korea, in the beginning of the pandemic, there was this guy who tested positive but refused to reveal his routes. This person A––it turned out he was married. He was with his mistress! Mistress B. Mistress B revealed her routes, and people realized hers overlapped with A’s. So there was an outcry. Privacy is not protected. This can’t happen in other countries, right? So [the route-tracking] doesn’t exist elsewhere. But in the Korean case, there are cons: If patient A went to a coffee shop one day while infected, people who turned out to have overlapped with him would seek testing to ease their anxiety, and this would prevent the spread by a lot. There was another confirmed patient, who ate at a restaurant with his sister-in-law, who came to be infected. Everyone who ate at the same place at the same time got tested. And Korean people were swarming in comment sections saying, “Why does he eat with his sister-in-law and not his wife?!”

B: Korean-Americans coming in are fine. Problematic are people who go out and meet with others when they are told to self-quarantine and then lie about it. [The government] checks if you’re quarantining by tracking your cell phone location data. But some people leave their phones at home and head out to avoid being tracked. So in Korea they’re considering using electronic wristbands, the ones you can’t take off––similar to the ankle monitors that track the movements of rapists, the criminals who’ve raped––so that these people would quarantine themselves right. But this raises human rights issues. […]

In Korea, confirmed patients are numbered––as Patient No. 1, No. 2, No. 3…––without their names being used. Those who were in contact with Patient No. 1, routes traveled by No. 1, and places where No. 1 stayed––all this information is gathered, and they test all those who’ve been exposed. For example, if No. 1 went to a bar, all those who were there at the same time are tested. If he went to work, all those at work are tested. If church, then all members. Family members as well. Such thorough testing, made possible by the availability of testing kits, prevents further spread of the virus. […] Korea has advanced IT infrastructures, with the fastest internet in the world. Using technology, the government has traced the routes of each patient, finding out which restaurants he ate at, which mall he shopped in, which bars he drank at, and which clubs he danced in while infected. Using his cell phone location data, credit card statements, and responses to questions, they get an overall picture, which help them disinfect the sites and test all those who’ve been exposed. The physical conditions of potential carriers are monitored through a cell phone application as well. Patient routes are made available to the public by text messages: “Patient No. 3 went to this restaurant in Haeundae” or “Patient No. 2 was at the Haeundae location of E-Mart from this time to that time on this day.” If I was at the same place at the same time, I would go get tested. One should also avoid going to that place for the time being.

I know that in other countries, the publication of transmission routes would be considered infringement of privacy; but in Korea, the name, date of birth, and address of each patient are legally protected. So they say this and that happened to “Patient No. 1.” Maybe acquaintances might be able to identify the patients, but most don’t know who they are. So the issue of privacy is not so big. Besides, what’s most important is the fact that people are getting infected on a large scale. To find the perfect solution for privacy rights would be impossible. All medicine has side effects. There is no perfect medicine without any side effects. We need to accept the side effects to cure the illness.

C: But to have all the private details exposed… That’s a little… I do think it’s violation of privacy. It’s way too detailed… To the extent I think it’s scary.

Mask purchases

A: And since there’s been a shortage of masks, only pharmacies were made to sell them so as to prevent hoarding. Pharmacies have access to the DUR (Drug Utilization Review) program that logs drugs purchased by an individual in order to prevent duplicate purchases of the same prescription. Mask purchases have been integrated to this program so that each person could only buy two per week. This has allowed masks to be supplied evenly. And some people who already have masks at home haven’t been buying so that those in need could get them. There’ve been considerate movements like this.

B: In Korea, when infections began, we were very low on masks. The virus landed here a month after it broke out in China, and during that time, because China didn’t have enough masks, they bought up Korean ones. They imported them, and their merchants came over and bought up masks from pharmacies and markets and took them back. Korea ran out of masks. This was the circumstance under which the pandemic broke out in Korea: with no masks. It was a mess, because people weren’t able to buy any. The government soon dictated that each person could buy two per week. Even so, lines would be too long at first. In Korea, every pharmacy is linked to hospitals and has access to digital records of who bought which drugs and when. Since such a system existed, mask purchases could be listed, too, right? For example, if I bought two masks at one place and tried to buy two more at another, I would be exposed. Pharmacies all over the country would know I bought two already––we have to bring our ID’s. The government sold masks to pharmacies only and had them manage sales systematically. At first, people would have to line up; now, they don’t have to––they can conveniently buy at any operating hour. Two per week. The government managed it well, so we don’t have issues. […]

The mask [rationing] policy is one of the things done well by the Korean government. In the U.S., a mask costs about what, 7-10 dollars? Do you know how much it costs in the United Arab Emirates right now? Two hundred dollars! That was a month ago. How much could it have risen by now? Even with the raised price, it’d be hard to buy one there. In Korea, a mask costs 1,500 won (~$1.21). Originally, it’s 4,000 to 5,000 won, but the government bought up the masks and made them available at a cheaper price. This means that every time a mask is purchased, the government loses about, say, 1,000 won, but they’re willing take that loss––because if the price of masks rises, it’d give citizens a hard time and create grievances. So the price is controlled––something they did well, right? […] Across the world, masks are the cheapest in Korea right now. The quality is the best, too. The 3M ones are so-so. Korean masks are comfortable––and they look nice, too.

C: Yes, I buy them every week, following the five group system*. I had bought some before for yellow dust** so I’ve supplemented with those, too.

*The rationing system in which residents are divided into five groups based on the last digits of their birth years, and each group is assigned a weekday for mask purchases

**Spring dust storms that originate from the Gobi Desert and combine with industrial pollutants on their way to Korea

Parliamentary elections (April 15)

A (May 9 follow-up): The election went well without issues. Infections didn’t increase because of it, so I suppose it was a successful election. Masks and gloves had to be worn. Vinyl gloves.

B (May 9 follow-up): The election didn’t cause any issue with prevention or infection. They prepared for it well, making sure people were sanitizing hands and wearing masks and gloves. The rallies were also done well without gathering too big a crowd. Fortunately, the cases were low in Korea around the time of the election. Had the cases been high, I don’t think they would’ve held the election, since it would’ve been dangerous to have people gather for voting. But cases had dwindled, and they had prepared thoroughly, so they managed the election well without issues.

C (May 9 follow-up): I voted. Fearing there’d be a lot of people, I put on a mask and voted early in the morning, when there’d be the least amount of people. If it began at 6am, and I went around 6:10am. Everyone was wearing masks, and the space between people in the line… Was it 50 centimeters? Not as wide as a meter. They marked the floor with footprint stickers so people could be distanced in line before voting. So we stood apart from one another and voted. Before entering, hands were sanitized, and they checked for masks and fevers, and once in, we were distanced.

American Response

American government response

B: The U.S. should look into [the mask rationing system of South Korea]. Even if one only needs five per week, it’s natural for them to be inclined to buy fifty when they’re in danger and panicking. Don’t you agree? Not knowing what’s to come, one’s bound to feel anxious without masks. Rich or not, everyone is equally vulnerable outside without a mask. So they’ll buy as many as they can. This means that no matter the amount a government acquires and makes available, there’ll always be a lack. In times when it’s difficult to even get two masks per week, as soon as stores are stocked with masks, people will buy in bulk like they do with toilet paper [in the U.S.]––and masks are more important than toilet paper. So masks should be sold at places that can control purchases, like pharmacies. I don’t know whether the U.S. already has a system [that prevents duplicate drug purchases] in place. Masks could be sold at hospitals, post offices, police stations, banks––public facilities that could be given access to purchase histories. Otherwise, there’ll be an outcry among citizens all year. […] The reason why [Americans] are making their own masks and using scarves is that they don’t have any available. The richest, most powerful nation in the world has the poorest [mask-wearing] practice! Don’t you agree? When a patient coughs with a cotton mask on, the virus is not filtered, infecting others. Masks should function to block the virus in both directions, inward and outward. If I’m the only one wearing a mask, it’s only half effective; it’s only truly effective when everyone wears masks. Cotton masks, without proper filters, lower the efficacy of the practice. […]

People in China have worn masks, even until now, and that alone has conquered much of the pandemic there. Masks block both the outward and inward flows of the virus––nothing else can do that. To not wear them– Even if there are cultural differences in Europe and America, it’s common sense to wear them. It’s too late by now. On the news today, I didn’t see anyone wearing masks on the marine vessel that arrived at the Port of New York. Not wearing masks is like going to war without guns. Masks are the most important thing. The American government is saying that washing hands is enough––nonsense! The virus is transmitted through droplets coming out of mouths. Why are we insisting on distancing in the first place? To prevent the droplets from entering our noses and mouths. Once they enter us, it’s too late. You can’t wash them out. Handwashing is mostly effective for indirect transmissions. Droplets should be feared, and they are not visible. Masks are the most important thing. Those who aren’t wearing masks shouldn’t be allowed to work at stores and offices nor enter them. Until the virus is controlled, one hundred percent of people should wear masks. This should be enforced strongly. Trump was finally forced to say masks should be worn… but he himself doesn’t wear one! That alone shows his character. Trump should be the one wearing a mask, first and foremost. Even Abe wears it now. Presidents should be seen wearing masks, for all their appearances. Politicians and journalists at briefings should wear them first to encourage the practice and raise awareness among the public. […]

Enforcing strict lockdowns like those in China might not be conceivable for Western countries that uphold democracy and individual rights. But when infection rates are so high like in New York City, Italy, France, and the U.K. right now, strong measures––for about 25 days––are necessary and effective. If the lockdown is partial, infections will continue, damaging the economy and lives for a much longer period. It might be more efficient to go into a complete lockdown for about a month. If there’s already a high number of cases, the Korean approach is not applicable, though Korea managed its wave of infections. It’s not applicable because Korea had been prepared, with testing kits widely available; as soon as the outbreak began, infections were tested right away and dealt with. Other countries have already had explosions of cases. So they should consider the kind of strict lockdown enforced in Italy right now. That’s being done in New York City right now, right? […]

I think what the American government did do well is closing schools early on in March, before the spikes in infections. It would’ve been a mess otherwise.

C: I hope they become more proactive about testing and treat patients quicker… It’s important to test as early as possible since the virus spreads so fast. I don’t think the U.S. government is as proactive as it should be. One person can spread to so many––the spread should be blocked right when the person begins to feel sick. To find out about the infection after one’s been sick and spreading the virus to many ends up tripling, quadrupling the overall effort required. So I think it’s important to test at the very onset of the infection.

Advice for the American people

A: They must be washing hands thoroughly already… I think wearing masks is effective in preventing infections. I saw on the news––you know how they wear shoes in their houses?––the microbes on your soles live on for a week.

B: It’s best to use good masks if possible. If not, make do with what you have––better than not wearing anything at all. Please don’t forget to wear. Put up a post-it with the word “mask” on your front door. […] While cases are high, eating inside restaurants would not be a good idea. Don’t hold gatherings like religious services, either. If you must enter an indoor space, try to have the windows open. […] Lessen physical greetings. No kissing! Oh, and until the pandemic is over, please replace all ‘f’ sounds with ‘p’ sounds like we do, to limit droplets spewing out.

C: I hope they wear masks more––it doesn’t seem they are good about it. But I think wearing masks really helps. From what I hear, even their president doesn’t like to wear them. Maybe it’s because they’re not used to masks as much and find them too uncomfortable. I think wearing masks is enormously preventative.

Looking Ahead

Experience so far

A: I wasn’t able to carry out my travel plans, nor have I been able to meet people I want to meet. My father is stuck at home, fearing he’d be infected if he goes outside. My mother says she feels like she’s in prison without being able to see her family. I’m not allowed to visit her at the hospital. When I go there to drop off food at the lobby, they measure my temperature and have me sanitize my hands. Because if the virus spreads at a hospital, it’d be a disaster. Patients have low immunity. A scary prospect.

B: What remain constant for me are my view that health comes first and the love I have for my family. Not too much has changed in Korea.

C: I want things to go back to the status quo. I want to return to my normal life. I love going to movie theaters, but I haven’t been able to go! I watch at home, which decreases the enjoyment to one fifth. You know how there are a lot of movie theaters in Korea? There’s one nearby so I’d go there a lot, but I haven’t been able to since we can’t go to enclosed spaces anymore… So I want to go to movie theaters, as well as other indoor places like gyms––back to my normal life. Oh, and I also want to travel! But I can’t, and I wonder when I’d be able to.

Society in the future

A: It’s nerve-racking, and we don’t know what will happen. But long ago, the Spanish flu––during which so many people died, and the economy was hit badly under similar circumstances––led to the development of technologies that equipped us better, they say. So there must be a good that will come out of all this. It might serve as a catalyst for social progress. Let’s hope for the quick development of a cure.

A (May 9 follow-up): I think there’ll be a movement toward domestic production as opposed to importation. Countries that have relied on other countries for masks lack them. So I think the production system will change such that essential products will be made within Korea. Companies like Samsung have been investing in factories in Vietnam and China, but [those countries] are not allowing technicians in because of the virus. In cases like that, in which factories like semiconductor factories are not running for a while, I heard that the loss is huge. Anticipating situations like that and beyond, companies will start building factories domestically, as experts say.

B (May 9 follow-up): There’ll be a greater interest in health and medicine: protective gear, masks, sanitizers, cures, vaccines, medical supplies… We saw global chaos due to shortages, didn’t we? It was a mess when masks weren’t available. People will want to be better prepared. […] This time, [we saw countries with] no tests kits, no masks, no sanitizers, no hazmat suits, with doctors and nurses going into wards wearing plastic bags. “Ah, we can’t have production bases abroad, in China, and import things anymore. We need to produce independently.” Especially essential goods like disinfectants, food, medicine, medical supplies, and hygienic products. Pandemics could happen again. Countries will start producing these things on their own to an extent and put aside some amount in preparation. […] Globalization will decrease. Traveling back-and-forth across borders and exports and imports will decrease over time. Policies will become isolationist. Travel and hotel industries will suffer. The pandemic will be a historical turning point––culturally, socially, and economically.

C (May 9 follow-up): Areas like the stock market are going in a new direction. Instead of stocks that used to be popular, stocks related to non-contact industries, like cyber payments, are on the rise. So I think society will develop in the direction of the non-contact––food deliveries, for example.

Life in the future

A (May 9 follow-up): After the pandemic is over, wouldn’t things return to normal? Since people feel so stifled. I think they’d want to restore what they had before. But I think they’ll be very weary of activities indoors. People will be careful at clubs, after the Itaewon outbreak––at underground businesses and clubs.

B (May 9 follow-up): The virus might not ever go away but become seasonal. Like the flu, it might live on with humankind, though it’s more dangerous and sneakier than the flu. And you know how they say there’ll be a second wave. […] Our lives… will be digitalized. Meetings and classes will be held online frequently. People will meet virtually over meeting in person. We will shop online over going to stores. The same applies to food delivery services. […] People will tend not to go to places where people gather. Much of it is psychological. Cars, for example, are available to sight, and we can try to avoid them. But we can’t see [the virus], right? I think there’ll be a heightened awareness of health and hygiene.

C (May 9 follow-up): In the case the virus doesn’t go away, I wonder, will we have to keep on living like this? We’ll be okay, but older people and sick patients––I worry about them the most, since [the virus] could be deadly for them. We’re not young, but I feel we could overcome [the virus] even if we catch it. We’d recover after getting sick. But I’m most worried about my parents and those with illness.

Concluding Remarks

I found during each round of interviews that all three interviewees were aware of the numbers of new and cumulative cases in Busan and South Korea at the time, at least in rounded figures. Overall, they were divergent in their views about privacy issues involved in the disclosure of patient routes, and unanimous in recommending mask-wearing to Americans and in deeming the execution of parliamentary elections successful. Their political leanings could be surmised from the extent to which they credited the Korean government for the nation’s relative success in combating the virus or from their remarks about entries from China at the beginning of the outbreak in Korea.

Interviewee B tended to play the role of a spokesperson for South Korea. He referred me to YouTube material multiple times for further information about the nation’s response. When responding to questions about personal experience, he would often depict the state of the city or the nation and address government measures in detail. (On the other hand, interviewee A tended to speak about trends on a societal level, such as voluntary rent reductions, if they moved her personally.) Interviewee B’s national pride is seen in many places, from his comparisons of Korea with other nations to his praise of Korean-made masks. Discrepancies might be telling as well: He expressed at one point that the social distancing policy in Korea was “too loose,” but asserted that it “befit[ted] a democratic society” later on. Despite the “risks” of foreign entries that he noted, he ultimately characterized Korea’s open border policy as an “inclusive” one “honoring the ideals of globalization.”

One of the instances in which my presence seemed to have influenced the responses in a pronounced way was when I asked interviewee B about Korean students overseas bringing infections into their homeland. He first said it was understandable that Korean students abroad would seek treatment back home. Later, he stopped himself mid-sentence while expressing that those entering with symptoms were problematic. It seemed to me at the time that his knowledge that his interlocutor herself was a Korean student in the U.S. who might end up considering such an option made him hesitant to express his judgment.

Photo Gallery

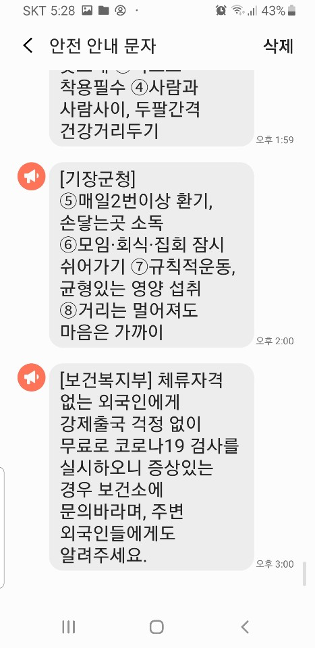

Figure 1: A text message sent by the Busan city government at 3pm on May 14, 2020 KST: “Foreigners without legal status can get COVID-19 tests for free without worrying about deportation. If experiencing symptoms, please contact a health center, and let the foreigners around you know as well.” The last numbered line from the previous set of messages, sent an hour earlier, deviates from the list of safety measures: “Distances are wide, but hearts remain close.”

Figure 2: From May 9, 2020 over several days, there has been an influx of similar text messages sent to the residents of Busan from the KCDC, the Ministry of Health, the Gyeongnam Provincial Government, and district offices of Busan, urging those who went clubbing in Seoul’s Itaewon area between April 24 and May 6 to get tested. For screenshots of some information shared by the Busan city government on the web, including patient routes, see the Pandemic City Snapshots section of this website.

Figure 3: An antimicrobial film and hand sanitizer inside the elevator of a residential building in Busan, a typical sight in the nation during the pandemic. District offices have distributed the films to buildings such as apartments, medical institutions, and welfare facilities. Photographed May 14, 2020.

Figure 4: “No Visitors,” “No Entry,” and “No Bathroom Use” signs posted on the entrance door of a nursing home in Busan. Photographed May 14, 2020.

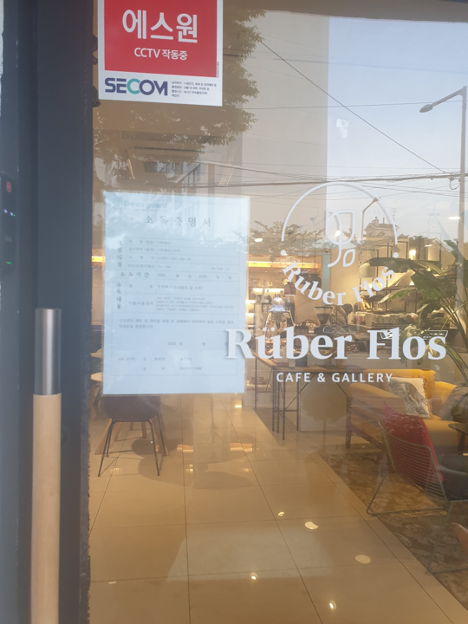

Figure 5: A coffee shop in Busan displaying a proof of disinfection. Photographed May 14, 2020.

Figure 6: The driver of the vehicle that transported a friend of C’s daughter from the Incheon Airport to the Gwangmyeong station, where she took the train (KTX) to Busan on April 1, 2020. The driver that drove C’s son on the same route when the son entered the country on May 11 wore the same gear. The son’s connecting domestic flight to Busan had been canceled to prevent his potential spread of the virus. On the train, those who just flew into Korea were put in a designated car, in which the occupancy of each row was limited to one person. Adjacent cars were left empty for the safety of the rest of the passengers. As soon as C’s son arrived at the Busan station, he was transported to a nearby testing center, at which he tested negative. After the test, the center made sure he was picked up; otherwise, he would have been provided a ride on a designated taxi or van so he would not go on public transportation.

Figure 7: The items that C’s son received the morning (May 12, 2020) after he entered the country include hand sanitizer, alcohol sprays, a thermometer, masks, and trash bags. A worker from the district health center brought them to his apartment and went through the items at the door after asking the son to come out with his mask on. During the mandatory 14-day quarantine, the son needs to record his temperature twice a day on the monitoring application he had to install at the airport and gets a call once a day from the district health center asking about his condition. On the last day of his quarantine, he is to leave his double-bagged garbage right outside his unit door for it to be picked up by the district health center. Different disposal protocols apply to those who tested positive or started showing symptoms during the quarantine period; their trash would be treated as biomedical waste.

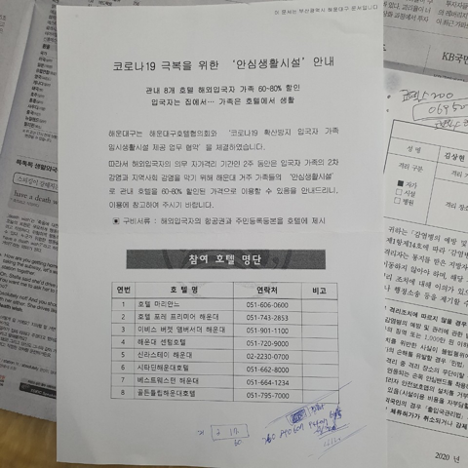

Figure 8: One of the information sheets inside the quarantine package given to C’s son lists the hotels in his district that offer 60-80% discounts to the families of those who just entered the country throughout the incoming member’s 14-day quarantine. Families must present the airline tickets of the individuals who just flew in. Photographed May 14, 2020.

Figure 9: The items in the box received by the friend of C’s daughter (the one who snapped Fig. 6) upon entering the country back on April 1, 2020, when there was a much larger influx of those returning to Korea from abroad. Some of the items were instant noodles, snacks, a book, and a magazine. “Unfair!” said C on behalf of her son.

Notes

[1] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황(5월 16일, 정례브리핑) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (May 16, daily briefing)], ” Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, May 16, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&act=view&list_no=367240.

[2] “신종코로나바이러스감염증 국내 발생 현황 (2월 6일, 정례브리핑) [Novel coronavirus: Current domestic case status (February 6, daily briefing)],” KCDC, February 6, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&act=view&list_no=366008.

[3] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황 (3월 14일, 정례브리핑) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (March 14, daily briefing)],” KCDC, March 14, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&act=view&list_no=366552.

[4] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황(4월 18일, 정례브리핑) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (April 18, daily briefing)],” KCDC, April 18, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&list_no=366942&act=view.

[5] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황(일일집계통계, 9시 기준) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (daily aggregate statistics, as of 9am)],” KCDC, April 28, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&list_no=366378&act=view; “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황(일일집계통계, 16시 기준) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (daily aggregate statistics, as of 4pm)],” KCDC, April 28, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&list_no=366388&act=view.

[6] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 국내 발생 현황(3월 15일, 0시 기준) [COVID-19: Current domestic case status (March 15, as of 12am)],” KCDC, March 15, 2020, https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015&act=view&list_no=366554.

[7] Chang Yŏn-je, “대구시 ‘신천지 교인 코로나19 검사 마무리 단계…시민 진단 확대’ [Daegu government says it nears end of COVID-19 testing of Shincheonji members and will expand tests of citizens],” Donga Ilbo, March 4, 2020, http://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20200304/99998192/2; “대구 신천지 검사 종료하니…신도 4200명, 비신도 1500명 확진 [Daegu’s Shincheonji testing over; 4,200 members and 1,500 non-members test positive],” Donga Ilbo, March 12, 2020, https://www.donga.com/news/Society/article/all/20200312/100122946/1; “코로나바이러스감염증-19 중앙재난안전대책본부 정례브리핑 (3월 3일) [Daily COVID-19 briefing by Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters (March 3)],” Ministry of Health and Welfare (South Korea), March 3, 2020, http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?contSeq=353310.

[8] Shin Chin-ho, “전세계 극찬 ‘드라이브 스루’…’1번’ 주치의 김진용 아이디어 [Family doctor of Patient No. 1 behind the globally acclaimed ‘drive-through’ idea],” JoongAng Ilbo, March 16, 2020, https://news.joins.com/article/23730620.

[9] “종교시설, 실내 체육시설, 유흥시설에 대한 15일 간 운영 중단 권고 [Recommendation for places of worship, indoor gyms, and entertainment facilities to suspend operations for 15 days],” MOHW, March 21, 2020, http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=353664.

[10] “대한민국 방역체계 [The quarantine system of South Korea],” MOHW, http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/baroView2.do.

[11] “2020학년 신학기 중,고3부터 순차적 온라인 개학 실시(코로나19) [The 2020 academic year to begin online, starting with third grades of middle and high schools (COVID-19),” Ministry of Education (South Korea), March 31, 2020, https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=340&boardSeq=80168&lev=0.

[12] No Chi-wŏn, “21대 총선 최종 투표율 66.2%… 28년 만에 최고 [The 21st general election turnout reaches 66.2%, highest in 28 years],” The Hankyoreh, April 15, 2020, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/assembly/937229.html#csidx9b8ba5fad610beb806a174557f73417.

[13] Yi Chun-hŭi, “미국 ESPN, 한국 프로야구 생중계한다 [ESPN of the U.S. to broadcast Korean professional baseball live],” May 4, 2020, The Hankyoreh, May 4, 2020, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/sports/baseball/943627.html.

[14] “중앙재난안전대책본부 정례브리핑(5.3.), 5월 6일부터 생활방역체계, 생활 속 거리 두기 단계로 전환합니다 [Daily briefing by the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters (May 3): We will switch over to the daily life quarantine/the ‘distancing in daily life’ phase from May 6],” MOHW, May 3, 2020, http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=3&brdGubun=31&board_id=311&ncvContSeq=2106&contSeq=2106&board_id=311&gubun=BDC.

[15] “코로나19 예방을 위한 유흥시설 집합금지명령 [Order banning operations of nightlife facilities for COVID-19 prevention],” Seoul Metropolitan Government, http://news.seoul.go.kr/welfare/archives/518401; Kang Tong-hun, “2020학년도 신학기 개학 연기 관련 브리핑(200317) [Briefing regarding the delay of the start of the 2020 academic year (March 17, 2020)],” Ministry of Education (South Korea), March 17, 2020, https://www.moe.go.kr/mnstrBoardView.do?boardID=430&boardSeq=80047&lev=0.

[16] Paek So-a, “이태원 클럽발 코로나 확진자 161명…’급격한 확산은 없어’ [Confirmed COVID-19 cases from Itaewon clubs reach 161, ‘without drastic spread,” The Hankyoreh, May 16, 2020, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/health/945197.html.

[17] “코로나바이러스감염증-19 부산시 상황알림(2020.2.21.21시 기준) 2명 [COVID-19: Busan status update (February 21, 2020, as of 9pm): 2 persons,” Busan Metropolitan City, February 21, 2020, http://www.busan.go.kr/health/corona3/1421966?curPage=1&srchBeginDt=2020-02-16&srchEndDt=2020-02-29&srchKey=sj&srchText=.

[18] “부산지역 코로나-19 확진자 현황 (2020. 5. 16. 17시 기준) 141명 [Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Busan (May 16, 2020, as of 5pm): 141 persons],” Busan Metropolitan City, May 16, 2020, http://www.busan.go.kr/health/corona3/1433788?curPage=&srchBeginDt=&srchEndDt=&srchKey=&srchText=.

[19] “부산지역 코로나-19 확진자 현황(2020. 4. 7. 17시 기준) 122명 [Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Busan (April 7, 2020, as of 5pm): 122 persons],” Busan Metropolitan City, April 7, 2020, http://www.busan.go.kr/health/corona3/1428668?curPage=&srchBeginDt=&srchEndDt=&srchKey=sj&srchText=4.%207.

[20] “부산지역 코로나-19 확진자 현황 (2020. 5. 9. 17시 기준) 138명 [Confirmed COVID-19 cases in Busan (May 9, 2020, as of 5pm): 138 persons],” Busan Metropolitan City, May 9, 2020, http://www.busan.go.kr/health/corona3/1432671?curPage=&srchBeginDt=&srchEndDt=&srchKey=sj&srchText=5.%209.